|

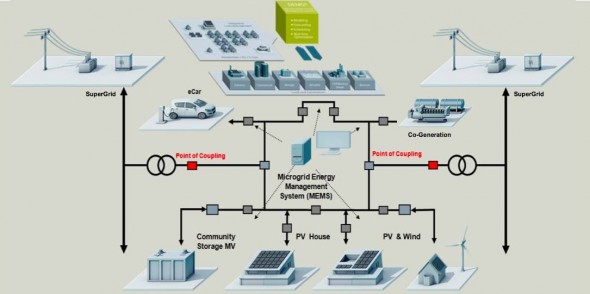

Australia’s energy markets are on the cusp of rapid change, but it is not just the prospect of individuals quitting the grid that represents the biggest challenge to industry incumbents: it’s the possible defection of whole towns and communities. The creation of micro-grids is seen by many leading players as an obvious solution to Australia’s soaring electricity costs, where the grid has to cover huge areas, at the cost of massive cross-subsidies that support it. The major network operators in Queensland, NSW, South Australia and Western Australia see micro-grids as an obvious solution to the challenge and cost of stringing networks out, sometimes more than 1,000km away from the source of generation. In Western Australia and Queensland, these subsidies amount to more than $500 a household. The cost of service to regional consumers in Queensland is far above the cost of service to those in the south-east corner. To address this, these states are proposing to take some small communities, and towns like Ravensthorpe in Western Australia off the grid. In New South Wales, some towns are taking the initiative themselves. In northern rivers region, the township of Tyalgum revealed it is considering a micro-grid that would allow it to largely, or entirely, look after its own energy needs. Indeed, the whole Byron shire is considering micro-grids as part of its efforts to become “zero net emissions” within the next decade, and to source 100 per cent of its electricity needs from renewables. But micro-grids are not just about grid defection. While it will make sense for those towns and communities at the edge of the network to become self-sufficient and disconnect entirely, most micro-grids will remain connected to the network, helping to reshape a centralised grid to one focused on more efficient decentralised renewable power generation sources and storage. Warner Priest, the head of emerging technologies at the Australian offices of German energy giant Siemens, says micro-grids are the innovative solution to our future smart grid needs. In fact, he notes, they were the original model for shared generation, but like electric vehicles they were swept aside by the push to big, centralized, fossil fuel generation, transmission and distribution. Now, through massive improvements in technology, it is becoming easier for remote and off-grid communities to look after their own energy needs without relying heavily on costly, imported energy derived from centralised fossil fuel sources. New sub-divisions may find it more cost-effective to never connect to the grid, and micro-grids could also be useful within major cities, addressing areas where the network is constrained by inadequate or end-of-life network assets. And within five to seven years, Priest says, these micro-grids could be completely renewable as new technologies such as on-site renewable hydrogen production become mainstream, replacing the non-renewable gas and diesel generation that is used as a micro-grid’s energy generation for when renewable energy sources are not available. Siemens Australia is drawing up plans for one 50MW micro-grid in Australia that would – ultimately – include up to 10,000 homes. It would comprise of some 40MW of rooftop solar (around ~4kW per home), an array of, centralised and decentralised battery storage, fossil fuelled gas generators, which could – within a few years – be replaced by renewable gas fuel such as hydrogen. The attraction comes through cost, resilience, reliability and efficiency. Fossil fuels burned at the point of consumption are two to three times more efficient than those burned at centralised power stations. That means more energy is harnessed from the equivalent fossil fuel, with ~50 per cent of that energy being in the form of thermal energy that is used for both heating and/or cooling. Priest says micro-grids are about integrating and balancing multiple loads and distributed generation resources within a smart micro distribution grid, using powerful software SCADA control systems (microgrid management systems), residential solar, wind energy, battery storage and other types of renewables and storage – such as hot water systems – ensuring that the use of fossil fuel gas and diesel is kept to a minimum. These micro-grids micro-grids currently run with the support of fossil fuels, but they will move to renewable fuels with the introduction of new technologies such as on-site production of renewable hydrogen using PEM electrolyzer technology. And, of course, battery storage.

“Within the next five to seven years, these micro-grids could be completely renewable,” Priest says. “That is not far away. The innovation and change is moving at a phenomenal pace. It is very exciting.” Priest says the idea of micro-grids is not about displacing traditional distribution and transmission networks; it’s about encompassing these new energy cells as distributed energy sources into the incumbent networks, with the ability to wheel power to remote energy consumers connected to the existing grid. Some micro-grids will remain islanded from the main utility grid, but most will retain some form of connection to allow bi-directional flows of energy – this for when the micro-grids draw on cheap energy, or for when they provide support to the existing distribution grid. “With DC coupled micro-grids, they would look like large 50MW batteries to the utility distribution grid,” Priest says. That means they will have a dual role of being be able to participate in the wholesale energy market, selling energy to the networks when optimal, and within the microgrid, retail energy to its consumers, topping up their own requirements from the utility distribution grid when wholesale energy is cheap. Article sourced from Renew Economy

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed